Agenor Hofmann-Delbor

Published in final, edited version at 2020-07-08 in The Journal of Internationalization and Localization

[Editorial, Agenor Hofmann-Delbor: this article was written in February 2020, just a few weeks before COVID hit the world hard. It’s interesting to see how quickly the perspective changes. Will we switch to this view again, once the virus is dealt with? Time will tell.]

Introduction: A conference as a site for synergy

As an industry watch opinion piece, this short article shares insights gained from many years of organizing technologically-inspired industry conferences, in particular, drawing on recent participant survey results from the Translation and Localization Conference (TLC) 2019. TLC has been held in Warsaw since 2012 as an annual international conference series. To maximize the opportunities for synergy presented by this annual gathering, the organizers have a special role during the event: on one hand, they must give the meeting a certain character and framework, and on the other hand, they must also let the creativity and wisdom of the conference delegates flow freely. New ideas that are generated at successful conferences reveal the power of collective intelligence. The article presents a perspective on current technological trends in the translation and localization sectors, followed by some of the results from the TLC 2019 participant survey, and personal reflections as a conclusion.

The eras of technological changes since 2000

Era of CATs

The period between 2000 and 2010 was clearly the era of CATs (computer-assisted translations). Suddenly, translation agencies and translators started to adopt a completely different way of working, which required new ways of thinking and sometimes new ways of paying for translation work. The first controversy arose: why should translators give discounts for high matches from translation memory tools? Challenges emerged: how to manage the quality of translations when a single translation memory is used by many people, etc. These were undoubtedly times of dynamic development for these tools, constant striving for efficiency gains, better design for ergonomics and improved work standards close to what CATs are today. It quickly became clear that the industry was able to develop only narrowly focused “internal” technologies with limited scope. Even with CATs, human translators had limited productivity and the commercial world was forever seeking a faster cycle. As the years went by, translators began to upgrade their work environment: there was a growing need to develop skills and become a Power User instead of simply a User, to learn automation, regular expressions and so forth. This trend is ongoing. A translator who wants to gain an edge over his or her colleagues is constantly moving with technology, becoming an expert in information processing, filtering, and building rules.

Era of Big Data

At the same time, the translation agencies have learned that it is almost impossible to run large-scale projects if you treat translator-subcontractors as separate entities. Although to this day almost all CAT systems can create project packages and send them for translation offline, for several years now the work of translation agencies and larger localization companies has been focused on sharing resources: connecting to the same dictionaries, the same translation memory, sometimes even the same documents. This way of working creates many challenges, but it is the modus operandi which is more attuned to the realities of today’s world. And it was about that time that the era of cloud computing and Big Data appeared on the horizon.

We all saw it in everyday life. Suddenly, we stopped using a particular server that was buzzing loudly in the studio rack and basically started using ANY server that might as well be a virtual entity scattered on different physical machines. The world accelerated even further, making almost every carry-on digital device a standalone powerful computer, often connected to the Internet and able to send messages and data and process information. The translation industry, as can be seen from examples such as database technology and predictive typing within the translation environment, loves to emulate the “big” industries. So when cloud computing stormed the IT industry and the data tsunami got a catchy marketing name, it became clear that the translation industry would soon be talking mainly about this topic. It also became a pretext for a quiet revolution in CAT tools and led to the emergence of online CATs, which are completely dependent on a constant presence in the virtual world.

Today, online CAT tools constitute an important part of the industry, although for several years after their development they still had not dominated the market. Although the concept in practice meant that the translator did not use a desktop solution, but rather a browser, it became clear that control over the process and data was equally important for clients and translation buyers. The subjects of control, copyrights, restricting, monitoring and blocking access, and limiting the translator’s freedom within the process remain controversial. In defence of translation agencies, it is worth noting that this goes hand in hand with many industry standards, particularly tmx and xliff, becoming more widespread. The standards mitigate chaos in data structures, and server technologies, including online CATs, provide many mechanisms for securing files.

Here it is worth going back to the other trend of this era: Big Data. Although the marketing messages were mainly based on the prospect of a gigantic number of new orders and increasing translation volume, the real effect of Big Data was to increase the effectiveness of various analytical activities in the world around us—something that would turn into Machine Learning and Deep Learning a few years later. It was an attempt to deal with a huge amount of information in a finite amount of time that made machines, algorithms and systems more and more effective in finding trends and recognizing the patterns and anomalies that so often govern our world.

Era of MT

Machine Translation (MT) has seen its popularity rise from time to time over the course of its history. The oldest machine translation systems existed in electromechanical form in the 1930s. Around 2010, localization companies at industry conferences promoted MT mainly by making best out of something which is far from perfect. Simple to use but highly unreliable technologies initially appeared as an alternative to CAT. It soon became clear that no technology in the industry can exist completely independent of the others and its potential benefit will only come to light when it is integrated into existing processes. However, this was not clear until some time later. First, MT companies and scientists reaped the benefits of the flood of data. Since we have a lot of data, let’s learn to use it. Maybe by throwing billions of sentences into the machine and observing statistical dependencies, we will find a way to improve the quality of automatic translation engines. That’s more or less what happened. The first effects were, for those days, astonishing. The renewed era of machine translation had come.

The industry, quite rightly, quickly saw the new quality of automatic translation as an opportunity to reach customers who would never pay for the professional translation of their products. The mythical profession of a post-editor emerged: a profession that every company still understands differently. One thing is certain: in the end, the entire process of translation had to be faster and cheaper from the customer’s perspective. Although almost every conference back then announced the end of translation in its traditional form in favour of post-editors, after several years passed, it became difficult to agree with such a statement. The real revolution and probably the biggest turmoil in the industry was to be caused by the technologies that were presented only in 2017, as we’ll follow up in the Discussion section.

Era of specialization

What happens when someone is constantly under pressure and sees only a dark future? They avoid the threat and go around it. From a conference organizer’s perspective, it was clear that translators became weary of technology talks at some point; the constant refrain that change was coming, that the good days were gone forever became overwhelming and demotivating for many translators. And the MT revolution, like any technological revolution, did not upend the lives of industry professionals overnight. Technologies tend to fill our lives like a dripping tap over a glass of water: gradually, imperceptibly, until finally we are immersed in them, not even knowing when it happened. But inside there is still a human, with a human mind, human experiences and human skills. Conferences have become focused on ways to emphasize the role of humans in the process, looking for a special, unsurpassed element for the machine. Something that brings translations to the highest quality level. Thus began the era of specialization. Just as earlier translators responded to the development of CAT tools by becoming Power Users, now they resorted to CPD, i.e. continuous development of professional skills, particularly specialization.

TLC’s conference themes over the last two decades reflect such shifts in focus. Since 2012, TLC’s conference delegates reflected on the impact of technology on human translation: conference themes included machine translation and the future of CAT tools, cloud computing and mobile technology, technical communication and big data, continuing professional development and specialization. Individual talks and workshops have addressed topics such as social media for translators, audiovisual translation, localization and project management, video game localization, and even invented languages. In these conferences, it was as if the world of translation were divided into distinct areas: the one where a machine does quite well, and the one where only a human can handle the task. As time lapsed, it became clear that the number of areas reserved for human beings was shrinking. This was also palpable from the survey results from the participants of TLC 2019, as we discuss next

The 2019 participant survey results

The TLC 2019 survey data was collected between March and June 2019 and the raw results were distributed online in July 2019 (see www.translation-conference.com). However, the fact that no detailed analysis of the data had been published before has led to the present article to discuss some of the key findings. We were motivated to bring into cognizance the key trends and insights which often remain hidden within the conference. Also, we wanted to satisfy our own curiosity to see if the views of such a mixed group (after all, TLC conferences are attended by freelancers as well as agencies, corporations, organizations, etc.) would converge as well as diverge. We were also interested to delve into participants’ deep concerns and whether they are able to suggest an interesting direction that will allow them to better cope with the changing world. And thus was born the idea of preparing an industry report based directly on the opinions and answers of conference participants.

TLC survey participants

Let’s first take a look at the participants who took part in the event in order to take into account the geographical, cultural and business aspects that can influence how particular trends and technologies are perceived. It is no secret that providers of different machine translation solutions primarily conduct research in the most popular language combinations, so it is often the case that only part of the translation industry or only selected regions come into contact with specific technologies. At the beginning of the survey, participants were divided into the following groups:

- Freelancer

- Translation agency employee

- Translation agency owner

- Translation buyer

- Translation department employee in a corporation

A total of 303 responses were collected from the TLC 2019 participants from 46 countries, although geographically, as the Translation and Localization Conference is an annual event held in Warsaw, Poland, most of the responses came from Europe: Poland, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Great Britain and Russia were the countries most represented. It is worth noting that although the Polish audience is best represented at this conference, they were not the majority of respondents. Naturally, however, it should be borne in mind that the general overtones of the survey may be biased towards markets more similar to Poland than dissimilar, for example, the USA or Japan.

Perceived opportunities and threats

Opportunities and threats like industry yin and yang are a good measure of moods, but also sometimes a clue for the future for specific groups of market participants. The aim of the report was to juxtapose two perspectives: freelancer and translation agency. We addressed the same question to these groups, suggesting some general possibilities (slightly differently for each group), while leaving room to give a different, custom answer.

Thinking about the future opportunities for translation agencies and localization companies, it occurred to us that new technologies are also an opportunity for new services, and the spread of MT will increase the overall demand for translation services (which is rather obvious). We also asked the agencies if they see opportunities in the various recent acquisitions and mergers in the market. Another direction would be to examine the technologies already in place, looking for a way to get more suggestions from resources (through more advanced searches for fuzzy segments) or all kinds of process automation (nowadays rather standard, but maybe there is still room for improvement?).

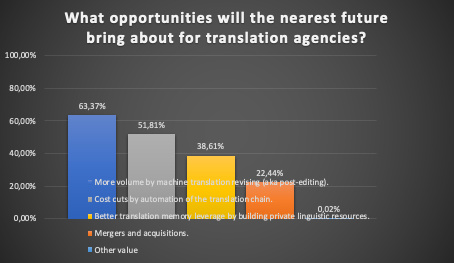

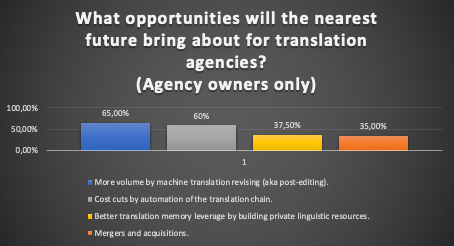

As shown in fig. 1, over 60% of the agencies believe MT will likely increase the overall translation volume. Furthermore, more than half (52%) the agencies want to see further process optimization and automation, and cost reduction. Only 38.61% of the agency representatives hope to extract more language resources than before, and only one in five foresees mergers with another company. When creating the survey, it occurred to us that translation agency employees (directors, project managers, location engineers), may look to the future a little differently than the owners, who bet their money on it. And the money spoke because if we narrow the results down to agency owners only, as in fig. 2, every third person in this group saw opportunities in acquisitions and mergers, and the degree of expectations placed on MT and cost-cutting was even higher.

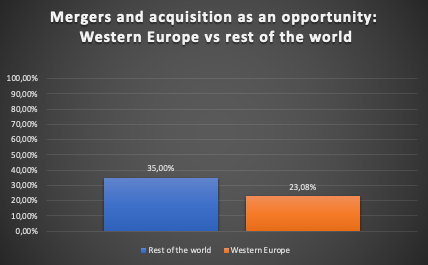

In turn, fig. 3 indicates that Western Europe looks at acquisitions less optimistically than the rest of the world. Our explanation is that this is because it is more difficult for mature markets to obtain such opportunities compared to markets that are still developing dynamically. Generally, in the responses from the agencies, there is evidence for increasing demand for translations through the use of MT, although the exact extent was not followed up in the survey.

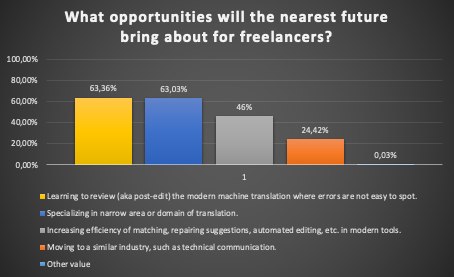

In the case of freelancers, we expected a different approach, because the fear of machines replacing humans is probably the most common thread sensed in any translation forum. However, fig. 4 illustrates that the translators in their replies showed something completely different. For the first time among the studies I know of, translators valued the chance to learn post-editing even higher than specialization. The difference is not big, at less than 0.4 percentage points, but it is worth noting that both these factors showed support from almost 2/3 of respondents. Less than half of the respondents believe in further increasing the effectiveness of CAT tools. Interestingly, only one in four freelancers is considering changing their profession or working in a related industry (e.g. as a technical writer).

Perhaps the most important conclusion of all the comments in the open-ended questions is that freelancers feel that creativity is the most important asset. This is the keyword for the coming years and the basic ammunition in the combat against machines. Translators believe in transcreation and copywriting, and they also believe that the power of imagination will give them the edge over machines for some time. What is more, they have actually also stopped looking at it in terms of competition: many of them have already incorporated MT into their everyday work routines without any harm to the prestige of their profession.

Industry sentiment: Preparing for the future

Undoubtedly, AI elements in everyday life will also increasingly become part of the translation industry. Every market participant will see them differently: the freelancer will work more and more as a reviewer or a linguistic subject matter expert, and the project manager will probably use the machine’s proposals as suggestions to facilitate the localization process or suggested subcontractors, since machine learning will allow project managers to analyze specializations, experiences, patterns in previous orders, evaluations, rates, quality, etc. It is also worth noting that the survey participants suggested simple and effective ways to enter the new translation reality. After all, you can learn how to use NMT, like any other technology, by attending training, reading articles or simply using it in your projects. However, only every fourth respondent, in general, is thinking about building a machine translation system on their own. This is hardly surprising, given that it will require access to considerable computing power, a huge corpus of data and specialized knowledge of machine learning. But if we look only at translation agencies, the result is quite different: almost half of the translation agencies are considering training their own MT engine.

It is also worth saying a few words about fears and anxieties in the industry. They are often the basis for frustration and misunderstanding, but if used well they can also be the source of motivation to prepare for change. Translation agencies evidently feel price pressures. Nearly 80% of agency representatives clearly fear aggressive competition and falling margins. Every second translation agency employee also sees a threat in the unstable quality of MT engines, and many of the agencies keep reporting that they have problems finding experienced and trustworthy translators. Among translators, the fear of a price war and lowering rates is even higher (83%), but for more than half, threat number two is the fear that increasing demand for machine translations may actually reduce the need for “human” translation in the long run. If one were to interpret this directly, it is certainly quite right. If a machine can do something right, there is no proper justification for having a human translator do it. However, the list of concerns summarized in this way does not take into account the fact that even a machine process very often requires a human input to verify the text. Translators are very interested in MT, even though they are afraid of it. This gives some hope for the near future.

Discussion: The era of machine learning and NMT

Over the years, industry professionals have all gotten used to meeting every year and listening to where the wind is blowing in the industry, often talking about how companies have reinvented the wheel, found a catchy name for a particular service, had visions of the end of their profession, etc. All this made the industry lose some dynamism and look at its own bubble a little less seriously. But everything changed at the end of 2017 when suddenly it turned out that the latest development in machine translation was no joke. As always, the first voices said, “Nah, I’ve heard so many times that a machine will replace me”. These same voices, however, quickly became silent, observing the effect of the new generation of machine translation engines. The era of machine learning and NMT (Neural MT) had arrived.

Huge processing power and access to linguistic data as parallel corpora made it possible to start looking at language differently than before. Since neural network systems are able to recognize faces in images, read text, remove noise from audio recordings, etc., they can also begin to process language (or actually its translation) as a kind of pattern. It soon turned out that this approach was extremely effective in improving the fluency and quality of the language generated by the machine. The market held its breath. Several solutions of this type appeared, which immediately gained great interest even among people who had never taken seriously the prospect of working with a text that has no physical author. During the course of the year, the industry was on its feet: NMT engines were used by translation agencies and freelancers on a scale that had never been seen before. At the same time, it became clear that the traditional translation model worked only by inertia.

Wait-and-see era

Now we have a wait-and-see era. Why wait-and-see? Well, because the initial hype for the technology is gone. It also seems that the engines themselves have experienced some natural developmental regression, constantly fed and improved, because customers want better, faster, more. And sometimes, especially with neural networks, two steps forward can equal three steps backwards. Or at least sideways. The fact is that a certain acceptable level of quality has stabilized for public engines. Or maybe our expectations were simply too high? Problems that still require the participation of professional translation agencies and translators, such as terminology, expertise, and substantive input into translation, have also become clearer. After more than two years with NMT technology, a certain consensus has been formed: “let’s focus on our thing, it is what it is.” This attitude seems to be the most common among conference participants. Nobody is trying to fight windmills anymore by questioning the sense of using CAT tools or MT: they have become our everyday life.

On the other hand, the industry decided to act like the three monkeys who see, hear and speak no evil. Models inherited from the reality of 20 years ago do not function properly in 2020. However, the industry is moving forward, ignoring voices that say something is not right. For customers, regardless of the era, translators remain inside the professional bubble. And buyers still just want a translation done yesterday—and preferably a good quality one, of course. Clients may say that what happens in the process sounds very fascinating, but in fact, they would just like to get a final document and an invoice for the service and move on.

Currently, work on NMT is focused on ensuring that the engine can be adapted on an ongoing basis: for example, to “teach” the system how to use established terminology or some corrections that are made ad hoc by a reviewer. The first such work was conducted in the previous generation of MT (SMT), but this technology does not work easily with engines based on neural network training. It seems, however, that we can expect ANMT (adaptive neural machine translation) systems at some point because the demand is huge. There is a chance that the improved suggestions or matches for translators within a CAT tool will not actually be implemented at the level of the engine, but rather in the next layer—at the stage of presenting the text in the editor. However, it is still not entirely clear how NMT will continue to change the market. For years now, there have been a huge number of websites and services that, by definition, are translated entirely automatically, and this fact is clearly indicated on the websites partially to justify the low quality, and partially to warn the user. At the same time, it also avoids any responsibility for errors and their consequences. The best-known example is Microsoft’s online help page, where the machine “processes” (this is probably a better term than “translates”) texts into different target languages for rarely used articles. If a support article is read more frequently, it will most likely end up as a job for a real (human) translator (or a reviewer, who will use the text produced by the machine instead of working from scratch).

Role of the reviewer

And since we are talking about a reviewer, the industry is stubbornly sticking to the term post-editor, underestimating the fact that correcting translations produced by the SMT engines of a few years ago is a completely different challenge than correcting texts generated by NMT. There is still no good idea how to do this. Yes, you can measure the time and speed of work. You can check the number of corrections and their time-consuming nature (e.g. methods referring to the edit distance), or you can base the evaluation on the opinion of a reviewer who will read a larger batch of text, based on her or his knowledge and experience in the field of translation. You can also combine everything together. The idea from many years ago that the work of the post-editor would “improve” the machine output on an ongoing basis is unlikely to work at this point because every significant change to the effects of the NMT engine requires re-training, but perhaps with the ideas to add adaptability to the process, it will return with new strength.

Then the role of the reviewer will also change. Not only will he or she be responsible for the text, but the person will also be a kind of mentor for the machine. This is an interesting perspective, but it also perfectly reflects the metaphor of sawing the branch you sit on. It is a long process, but the better the MT quality, the less reviewing is needed. Of course, this is a great simplification, but already in the era of the classic Translation-Editing-Proofreading (TEP) model, many reviewers would over-report preferential changes in the text as a way of justifying their role in the process. It is easy to imagine the hesitation of a reviewer who has to return a text checked after (A)NMT with the comment “all right, no changes to the text are required”. For the time being, however, there is a long way to go, and the translation industry and academia still do not quite know who this MT reviewer might be. To highlight the human element, some voices call this position “MT Enhancer”. Many companies still stubbornly call such a position a post-editor and even use the same billing models that functioned during the SMT era, usually simply paying the translator a fraction of the standard salary in the name of the principle that using the machine means the cost will be much less. Sometimes this is true, but sometimes it is not. However, the fact is that the quality of the resulting text is improving. Logic dictates that the quality can only get better. It is also possible that it will stabilize at a certain level for several years.

In conclusion: for interesting times

Even the greatest industry visionaries cannot predict what will happen next. However, if the current reality of the “waiting era” is to continue for at least several years, how should we approach the translation process and prepare reviewers? There is no doubt that today the industry consensus states that good quality translation memories are still a valuable resource (although not as valuable as they used to be). The importance of fuzzy segments, i.e. those that contain only a fragment of the sentence currently being translated, is decreasing. At some point, it is faster to improve a machine translated segment than a fuzzy match. Today, it is probably the so-called low fuzzy (70-84%), but we can confidently assume that soon only high fuzzy (95-99%) and Exact Match segments (100%) will count. Below these values, the machine will most likely be better at processing the whole sentence, because the entire sentence will be based on the full source text, while low fuzzy matches from TM can be very different and difficult to edit to the necessary wording. It is also possible that the upcoming next evolution of CATs will bring the first attempts to combine suggestions from the translation memory with suggestions (translations) from the MT engine. This would certainly be something that would have a lot of justification in the current technological reality.

However, it is still unclear what to do with the reviewer. As the quality of machine-translated texts is improving, the perspective of a decreasing number of amendments is logical and confirmed by the opinion of those who have been working with NMT texts for a long time (which was one of the conclusions of the MT session run by Bireta Translation Agency at the 2019 TLC conference regarding the findings from using NMT in real-life projects). Fewer corrections, paradoxically, means a greater challenge for the reviewer, because it basically puts him or her to sleep. It is much easier to overlook one incorrect translation segment among 100 correct ones than when the ratio is one in five. There are also different types of errors. NMT engines generate a fluent text whose language is almost as idiomatic as that of a native speaker (the article you’re reading was based on such a translation!), but sometimes they happen to completely change the meaning of the translation such as omitting a negation. In extreme cases, this can mean that space is fired into a rocket instead of a rocket into space, or that the dose of a drug should be reduced instead of increased.

From a conference organiser’s perspective, the trends and eras discussed in this article have been clearly visible in recent years and they are still apparent today, converging in different areas. Occasionally, there is a project that completely follows the classic, somewhat archaic model with a translator and a proofreader both using CAT tools. Currently, the question about using MT in large projects is no longer whether we should do it, but how and to what degree. And yet it applies to just a fragment of the translation market. Progress in technology goes far beyond text processing: text dictation (automatic speech recognition) and remote interpreting services via speech to speech MT are no longer rarity.

In the novel Interesting Times, Sir Terry Pratchett used the saying “may you live in interesting times” as a curse. Undoubtedly interesting times have come, but everything seems to indicate that the most interesting (and the most terrifying?) is yet to come.

Agenor Hofmann-Delbor, PhD., Head of the Organizing Committee of the Translation and Localization Conference in 2011-2020, and a Managing Director of Localize.pl.

Szczecin, Poland, 2020-02-02